EBK Home

Kingdoms

Royalty

Saints

Pedigrees

Archaeology

King Arthur

Adversaries

For Kids

Mail David

Brixworth

The Date of the Church Reconsidered

Northamptonshire is an area particularly rich in Anglo-Saxon churches and church remains. Although the higher proportion of Anglo-Saxon remains may lend itself to the potential for architectural diversity, it has been suggested that the masons of Northamptonshire were "architectural pioneer[s]". In spite of this pioneering spirit, which may be based on the innovations at Brixworth, have architectural historians let down their critical guard in accepting the date of the building based on the writings of a monk who wrote almost 500 years after the building was supposedly constructed? Has the Church of All Saints at Brixworth become the subject of circular analysis? Because historians have accepted the date of AD 675 as the foundation of the building, they have looked at the features that are typically found in structures of a later date and called the Brixworth builders pioneers. Were the builders of Brixworth "architectural pioneers" or was the building actually built at a later date? The archaeology and documents relating to the building will be examined as will other possible stylistic sources. The examination will reveal a connection not only with the Kentish group which was initially believed to be the closest stylistic source but also with the later Northumbrian group as well as Carolingian influences.

The

archaeological evidence is inconclusive. There were archaeological

excavations held near the church in the early 1980s. A large ditch was

discovered that has been dated to the late seventh or early eighth

century. It has been suggested that this ditch was the boundary of the

monastery. The ditch does not necessarily indicate a monastery was present

at that time, and provides no information about the present structure. A

late Saxon cemetery was also discovered adjacent to the ditch. The

presence of the cemetery, which has been dated to a later period than has

the ditch, does not necessarily indicate that there was a monastic

foundation on the site at the time the ditch was made; however, a possible

earlier foundation can not be ruled out by this archaeological evidence

either.

The

archaeological evidence is inconclusive. There were archaeological

excavations held near the church in the early 1980s. A large ditch was

discovered that has been dated to the late seventh or early eighth

century. It has been suggested that this ditch was the boundary of the

monastery. The ditch does not necessarily indicate a monastery was present

at that time, and provides no information about the present structure. A

late Saxon cemetery was also discovered adjacent to the ditch. The

presence of the cemetery, which has been dated to a later period than has

the ditch, does not necessarily indicate that there was a monastic

foundation on the site at the time the ditch was made; however, a possible

earlier foundation can not be ruled out by this archaeological evidence

either.

Like the archaeological sources, the written sources are also inconclusive. Although the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle supports the foundation of several daughter Abbeys of Medeshamstede (later known as Peterborough), it does not specifically state Brixworth in its list of foundations. The building apparently stood in ruins in the 10th century, possibly as the result of the Danish raid. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle does mention a Danish raid that would have likely torn through Brixworth. An entry in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states the following:

In this year [869/70] the host went across Mercia into East Anglia, and took winter quarters at Thetford; and the same winter St. Edmund the king fought against them, and the Danes won the victory, and they slew the king and overran the entire kingdom, and destroyed all the monasteries to which they came.

By the end of the tenth century, the building seems to have been made suitable for use. At the time the Domesday Book was compiled in 1086, the monastic use of the building appears to have ceased. Domesday Book reports that Brixworth was a manner with one priest, 14 villagers and 15 small holders. The next mention of Brixworth is in the writings of a twelfth century monk, Hugo Candidus. Hugo expanded on the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's list of monastic establishments. He too wrote that the monastery at Medeshamstede founded many daughter houses, but added Brixworth to the list. According to Hugo, Brixworth was founded by Sexwulf and Cuthbald who were known to have been late seventh century Abbots at Medeshamstede. Although Hugo was not a contemporary of Cuthbald or Sexwulf, he may be right in assigning a late seventh century date to the founding of a monastery at Brixworth; however, it does not necessarily date the present building. Hugo's testimony is a large factor in assigning the date of construction at c. 675. Hugo has largely been accepted because his assertion that Brixworth was founded as a minster is supported by its size.

It is generally

accepted that the Church of All Saints at Brixworth was built as a minster

but the conventions of the structure itself do not clearly fall into any

established tradition of construction. There were established conventions

and traditions on which builders could draw. These traditions were

accepted within the time frame and the geographic region. The established

styles are mere guidelines and do not necessarily exclude any other

possible sources or the possibility for creativity on the part of the

building's designer, but as the Anglo-Saxon builders were unfamiliar with

stone construction, it is reasonable to assume that they would  have

built in styles familiar to them. There are four likely sources that the

Brixworth masons could have drawn on for a monastery or church built circa

AD 675: the Romano-British School, such as Silchester; the Anglo-Saxon

School, such as Escomb; the Kentish School, such as St. Augustine,

Canterbury; or possibly the Northumbrian School, such as Jarrow.

have

built in styles familiar to them. There are four likely sources that the

Brixworth masons could have drawn on for a monastery or church built circa

AD 675: the Romano-British School, such as Silchester; the Anglo-Saxon

School, such as Escomb; the Kentish School, such as St. Augustine,

Canterbury; or possibly the Northumbrian School, such as Jarrow.

The Romano-British

style is represented in what is believed to be the earliest building

constructed in England for Christian services: the basilica at Silchester

(Hampshire). It was of the basilican plan with an apse at the west end and

an eastern narthex. The Anglo- Saxons did not, however, adopt this plan

for their Christian buildings. The usual Anglo-Saxon church plan was

generally quite plain. The plans of Bradford-on-Avon

(Wiltshire) and Escomb (Co. Durham) show a square ended chancel divided by

a solid wall with a narrow arch. Porches on the north and south were not

uncommon. The Kentish school had standard methods of design and

construction. Its design was based on the Roman basilican form. The

basilican plan was probably  reintroduced

in England by Augustine in 597. It was Augustine who summoned builders to

England from Gaul to build "in the Roman manner." The last

stylistic source in England for Brixworth is the Northumbrian School. In

674 Benedict Biscop, an Anglian noble who had been a monk in France,

brought French stone masons to the north of England and began construction

of stone churches. The monasteries at Monkwearmouth and Jarrow are

examples of the Northumbrian School. Northern structures such as Hexham,

Jarrow and Monkwearmouth, were similar to Gaulish basilicas.

reintroduced

in England by Augustine in 597. It was Augustine who summoned builders to

England from Gaul to build "in the Roman manner." The last

stylistic source in England for Brixworth is the Northumbrian School. In

674 Benedict Biscop, an Anglian noble who had been a monk in France,

brought French stone masons to the north of England and began construction

of stone churches. The monasteries at Monkwearmouth and Jarrow are

examples of the Northumbrian School. Northern structures such as Hexham,

Jarrow and Monkwearmouth, were similar to Gaulish basilicas.

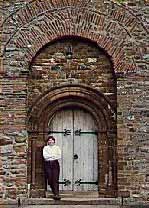

Brixworth does not fall

neatly into any model. The building generally follows the basilican plan.

The main structure is built on a 3:1 ratio plus a west porch and an

apsidal chancel. An upper room in the narthex has a three-light window

with a pair of late Saxon baluster shafts separating the lights (see image

on the right) which are similar to those at Monkwearmouth. The west end

window at Brixworth has a modified form of a Byzantine architectural

technique which was not adopted in Italy until the end of the ninth

century and Germany in the tenth century. The nave has four bays and was

flanked to the north and to the south with structures which were

originally believed to be side aisles, but more recent archaeological

evidence has  revealed

that the large side arches provided access into side chapels or porticus,

similar to those at Canterbury St. Augustine or the north side of Jarrow,

rather than side aisles as understood in the traditional basilican form.

It was later in the Saxon period that the chapels were altered to form

side aisles. After the side aisles were destroyed, what was once the

interior arcade, was bricked up and served as the outer wall. This

arcading is closely related to Jarrow of the Northumbrian group.

revealed

that the large side arches provided access into side chapels or porticus,

similar to those at Canterbury St. Augustine or the north side of Jarrow,

rather than side aisles as understood in the traditional basilican form.

It was later in the Saxon period that the chapels were altered to form

side aisles. After the side aisles were destroyed, what was once the

interior arcade, was bricked up and served as the outer wall. This

arcading is closely related to Jarrow of the Northumbrian group.

The triple chancel

arcade is an important feature as it stylistically ties Brixworth to the

early Kentish School. It was also originally believed that a triple arcade

opened up into the presbytery, but once again, more recent scholarship has

reinterpreted the evidence and has suggested an alternative. It was

initially asserted that the inclusion of a triple arcade chancel arch

indicated a close relationship with the Kentish group; however, the  triple

arcade chancel arch theory has been set aside in favour of a five

"window" opening. Conclusive evidence is not possible, however,

due to later renovations. In addition to the triple chancel arch, the apse

also indicated a close relationship with the Kentish group. The apse was

not popular in England, although it was a characteristic of the Kentish

group. The apse was originally semi-circular, but was later modified into

a polygonal shape on the outside. The crypt ambulatory dates from the

original apse but is usually assigned a late eighth or early ninth century

because, with the exception of Brixworth, this style of ambulatory was not

known until that period.

triple

arcade chancel arch theory has been set aside in favour of a five

"window" opening. Conclusive evidence is not possible, however,

due to later renovations. In addition to the triple chancel arch, the apse

also indicated a close relationship with the Kentish group. The apse was

not popular in England, although it was a characteristic of the Kentish

group. The apse was originally semi-circular, but was later modified into

a polygonal shape on the outside. The crypt ambulatory dates from the

original apse but is usually assigned a late eighth or early ninth century

because, with the exception of Brixworth, this style of ambulatory was not

known until that period.

Brixworth has a subterranean ambulatory of a non-existent crypt under the sanctuary. Crypts are rare in Saxon churches and suggests an Italian or a Carolingian influence. The purpose of the ambulatory is not clear. It may have been used to house relics and the walkway would have provided access for the pilgrims. There is relic that is said to have come from the body of the eighth century Anglo-Saxon missionary, Boniface. It has been suggested that the crypt was built to house this particular relic. An alternative suggestion has been made recently, and that is that the crypt may have been designed for burial use. There are niches that may have been deliberately constructed for the purpose of receiving stone sarcophagi. There is no trace of the crypt under the apse itself. Perhaps the construction of the crypt was interrupted by the Danish invasion of the area, which suggests a later date of construction as the crypt ambulatory and the apse were contemporary.

Although the crypt is rare in Anglo-Saxon architecture, there are other examples to be found in England, such as the ninth century Church of All Saints in Wing (Buckinghamshire). Brixworth and Wing share some common features and may have been built about the same time. The basic basilican plan, 3:1 length:width ratio, apsidal chancel, non-radiating voussoirs, three course imposts and a crypt. Many of these features were rare in Anglo-Saxon architecture, but are present in both churches. Wing has been dated to the ninth century based mainly on its design and the inclusion of the apsidal crypt, a Carolingian innovation. Brixworth shares many of these features, including the characteristic ninth century Carolingian outer crypt, yet it has been assigned an earlier date. The main difference being a written source places Brixworth in the seventh century and no such source exists for Wing.

In

many cases, written sources provide valuable details that may not be

gained from any other source; however, in cases such as Brixworth, the

other sources are largely ignored in the presence of written evidence.

Other buildings with similar features are assigned later dates in the

absence of written records. There are similarities between Brixworth and

the Northumbrian group, which was established in 674. Given the relative

geographic positions, it is unlikely that the Northumbrian influence would

have made its way as far south as Brixworth by the time Hugo Candidus

claims that Brixworth was built in the late seventh century. There is

nothing to suggest that Benedict Biscop stopped in Brixworth on his way to

Northumbria. There is also strong evidence of the Carolingian influence,

particularly in the crypt. This influence may have found its way into

England through a direct link between the ninth century Carolingian court

and the kingdom of nearby Wessex. King Egbert of Wessex grew up in the

court of Charlemagne and returned to England in 802. It is possible that,

due to Britain's insular nature, an architectural style such as Brixworth

could have been developed; however, logic suggests that if these features

are found in abundance elsewhere at a later date, that perhaps the date

given is too early and that Brixworth adopted Northumbrian and Carolingian

features rather than the other way around.

In

many cases, written sources provide valuable details that may not be

gained from any other source; however, in cases such as Brixworth, the

other sources are largely ignored in the presence of written evidence.

Other buildings with similar features are assigned later dates in the

absence of written records. There are similarities between Brixworth and

the Northumbrian group, which was established in 674. Given the relative

geographic positions, it is unlikely that the Northumbrian influence would

have made its way as far south as Brixworth by the time Hugo Candidus

claims that Brixworth was built in the late seventh century. There is

nothing to suggest that Benedict Biscop stopped in Brixworth on his way to

Northumbria. There is also strong evidence of the Carolingian influence,

particularly in the crypt. This influence may have found its way into

England through a direct link between the ninth century Carolingian court

and the kingdom of nearby Wessex. King Egbert of Wessex grew up in the

court of Charlemagne and returned to England in 802. It is possible that,

due to Britain's insular nature, an architectural style such as Brixworth

could have been developed; however, logic suggests that if these features

are found in abundance elsewhere at a later date, that perhaps the date

given is too early and that Brixworth adopted Northumbrian and Carolingian

features rather than the other way around.

Article by Stephanie James

Sources

William Addison (1982) Local Styles of the English Parish Church

Mervyn Blatch (1974) Parish Churches of England

Russell Chamberlin (1993) The English Parish Church

A.W. Clapham (1969) Romanesque Architecture: Before the Conquest

G.H. Cook (1961) The English Medieval Parish Church

J. Cox (1944) The Parish Churches of England

P.H. Ditchfield (1975) The Village Church

G.M. Durant (1965) Landscape with Churches

Eric Fernie (1983) The Architecture of the Anglo-Saxons

Richard Foster (1981) Discovering English Churches

G.N. Garmonsway (1990) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

F.E. Howard 1936) The Medieval Styles of the English Parish Church: A

Survey of their Development, Design and Features

Leonora Ison & Walter Ison (1972) English Church Architecture

Through the Ages

Nigel Kerr & Mary Kerr (1982) A Guide to Anglo-Saxon Sites

Frank Thorn & Caroline Thorn (1979) Domesday Book:

Northamptonshire, Vol. 21

H.M. Taylor & Joan Taylor (1965) Anglo-Saxon Architecture, Vol. 1

H.M. Taylor (1978) Anglo-Saxon Architecture, Vol. 3

David M. Wilson (1986) Anglo-Saxon Art: From the Seventh Century to

the Norman Conquest

Part 1: History of the Church