EBK Home

Kingdoms

Royalty

Saints

Pedigrees

Archaeology

King Arthur

Adversaries

For Kids

Mail David

St. Mary's Church, Deerhurst

Founded circa AD 800

Little is known of the history of

the place. Architecturally, it appears to have been established in the

late seventh century, but there are no records of its existence before

804. That year, Aethelric, son of Earl Aethelmund of Hwicce (a Saxon

sub-kingdom covering this area) granted the priory a very large area of

land and made known his desire to be buried there. It has been suggested

that the priory was always the main church of the Hwicce and that there

Kings were traditionally buried here. It was certainly the scene of

important political events like the 1016 signing of the treaty between

Kings Edmund

Ironside and Canute

which divided England in two.

Little is known of the history of

the place. Architecturally, it appears to have been established in the

late seventh century, but there are no records of its existence before

804. That year, Aethelric, son of Earl Aethelmund of Hwicce (a Saxon

sub-kingdom covering this area) granted the priory a very large area of

land and made known his desire to be buried there. It has been suggested

that the priory was always the main church of the Hwicce and that there

Kings were traditionally buried here. It was certainly the scene of

important political events like the 1016 signing of the treaty between

Kings Edmund

Ironside and Canute

which divided England in two.

It is the church itself which tells us most about the building's story. It started as a rectangular building with a western porch in the late seventh century. A circular apse and side chapels were added early the following century. In the 9th century the apse was rebuilt as a polygon and individual chapels extended all the way down both sides. The 10th century saw the western porch extended to form a tower and it is from here that you enter St. Mary's.

Inside, on the wall opposite, there

is an early carving of the Virgin and Child with traces of its original

paintwork still intact. It may have come from the ruined apse. As you move

forward towards the nave, turn to examine the very fine wolf-head

dripstone terminals either side of the doorway. They were very sensibly

moved here from the outside wall in 1860 to protect them from the ravages

of the British weather. There are further Saxon wolf-heads either side of

the altar. In puritan times, this was placed centrally in the church,

hence the survival

of the unique pew arrangement at the eastern end of the building. The main

features of the nave are the exceptional examples of Early English

arcading with delightfully carved corbels and capitals, but turn again and

look up at the western church wall for more Saxon details. The highest

feature is a possible dedication stone. Below this sits what is said to be

the "finest, most elaborate opening in any Saxon Church":

certainly an excellent example of Saxon pointed windows. Then there is a

bizarre triangular window next to a small Saxon doorway which opened onto

a western gallery. The old Saxon building was largely based on two

storeys. On the ground-floor is a good Saxon archway.

Inside, on the wall opposite, there

is an early carving of the Virgin and Child with traces of its original

paintwork still intact. It may have come from the ruined apse. As you move

forward towards the nave, turn to examine the very fine wolf-head

dripstone terminals either side of the doorway. They were very sensibly

moved here from the outside wall in 1860 to protect them from the ravages

of the British weather. There are further Saxon wolf-heads either side of

the altar. In puritan times, this was placed centrally in the church,

hence the survival

of the unique pew arrangement at the eastern end of the building. The main

features of the nave are the exceptional examples of Early English

arcading with delightfully carved corbels and capitals, but turn again and

look up at the western church wall for more Saxon details. The highest

feature is a possible dedication stone. Below this sits what is said to be

the "finest, most elaborate opening in any Saxon Church":

certainly an excellent example of Saxon pointed windows. Then there is a

bizarre triangular window next to a small Saxon doorway which opened onto

a western gallery. The old Saxon building was largely based on two

storeys. On the ground-floor is a good Saxon archway.

The north and south aisles house

further treasures. The western window of the latter has what remains of

the church's impressive array of old glass. St. Catherine is easily

identified with her famous wheel. She dates from around 1300. Accompanying

her is a mid 15th century depiction of St. Alphege, an 11th century monk

from the priory who rose to be Archbishop of Canterbury and was martyred

by the Danes. There are also arms of the De Clare Lords of Tewkesbury,

kneeling members of the De Hautville family and 'Suns-in-Splendour'

indicating the parish's Yorkist sympathies during the Wars of the Roses.

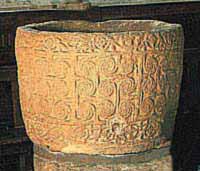

In the north aisle is the superb ninth century font, rescued last century

from a farmyard. It shows heavy Welsh influence being decorated mainly

with so-called Celtic Trumpet Spirals. The Strickland memorial window

nearby shows the family's turkey  crest. An ancestor is said to have

accompanied the Cabots to America and introduced the bird to Britain on

their return. Further east are the handsome brasses of the Cassey family

from Wightfield Manor. Sir John was Chief Lord of the Exchequer in the

late 14th century,

but it is the little dog at the feet of his wife which draws attention. It

is obviously the depiction of a specific family pet, for he is named as

'Terri': the only example of a named animal on any memorial brass. The

walls of the church in this area were stripped in 1973 to show the Saxon

stonework. They give a fascinating insight into the building's original

form, showing two of the doorways to the numerous side chapels or 'portici'

and holes for the wooden Saxon scaffolding!

crest. An ancestor is said to have

accompanied the Cabots to America and introduced the bird to Britain on

their return. Further east are the handsome brasses of the Cassey family

from Wightfield Manor. Sir John was Chief Lord of the Exchequer in the

late 14th century,

but it is the little dog at the feet of his wife which draws attention. It

is obviously the depiction of a specific family pet, for he is named as

'Terri': the only example of a named animal on any memorial brass. The

walls of the church in this area were stripped in 1973 to show the Saxon

stonework. They give a fascinating insight into the building's original

form, showing two of the doorways to the numerous side chapels or 'portici'

and holes for the wooden Saxon scaffolding!

See also: Odda's Chapel