EBK Home

Kingdoms

Royalty

Saints

Pedigrees

Archaeology

King Arthur

Adversaries

For Kids

Mail David

St.

Mary's Church,

St.

Mary's Church,Sompting

Architectural Details

The

Tower

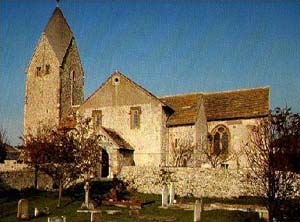

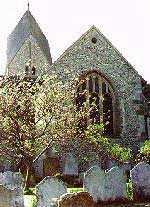

The Church of St. Mary in Sompting is one of the most striking examples of

Anglo-Saxon architecture in all of England. Its primary distinguishing

feature is the Rhenish Helm or

Rhineland Helmet of the tower. This is the only known example of this

style with roots in the Anglo-Saxon period.

The tower is best seen from the outside, where the helmet shape of the roof will be noticed, as well as the small Saxon windows high in the walls, and the stone pilaster strips in the centre of each wall and at the corners. The walls are of solid masonry and stand on a natural chalk foundation.

Inside the tower, the arch is an important example of Saxon architecture, built by men who had seen Roman arches still standing in Sussex. An altar stood against the east wall of the tower, and the arch is therefore not in the centre of the wall.

The

Nave

The

Nave

Mentioned in the Domesday Book of AD 1086, the Church was granted to the

Order of the Temple of Soloman in AD 1154. The Order was a crusading group

of monks commonly known as the Templars. Soon after they were granted the

Church, they rebuilt the nave and chancel on the original Saxon plan with

the walls in one straight line with the tower walls. They added the

present north and south transepts, originally walled off from the main

church, as chapels for the use of their members. Many of their small

Norman windows have been replaced at various dates by the present larger

windows. In a blocked doorway on the north side of the nave carved stones

have been placed so that the back and front can both be seen: the back

faces west and shows Saxon carving, while the front facing east shows a

13th century carving of Our Lord in Majesty.

The

North Transept

This was originally a separate chapel for the use of the Templars. Notice

the central pillar supporting the vaulted roofs of the two small chapels

to the east, the southern one which would have served as the chancel. A

corbel carved with a strange face supports the vaulting of the roof

between the chapels. In the west wall are traces of an original Norman

window discovered in 1969. There are memorials to the Crofts and Tristram

families here.

The

Chancel

It

will be noticed that there is no arch separating the nave and chancel.On

the north wall is the carved tomb of Richard Burre who died in 1527, a

member of London Guild Companies. Made in a simple style, the tomb was

planned to be used as an Easter Sepulchre, and to replace the earlier

example still seen a little to the east as a small recess ornamented

with a strip of Saxon carving. Low down in the corners of the east wall

are two hollows known as aumbries which were probably used to contain

relics. In the south wall near the altar is the piscina once used for

washing the chalice and paten after Communion Services: two strips of

Saxon carving ornament the top. The blocked opening in the south wall is

thought to have connected with the lower level of the south transept.

Behind the altar the elaborately carved reredos of soft limestone is

considered to be a good example of Victorian craftsmanship, as are the

stained-glass windows.

It

will be noticed that there is no arch separating the nave and chancel.On

the north wall is the carved tomb of Richard Burre who died in 1527, a

member of London Guild Companies. Made in a simple style, the tomb was

planned to be used as an Easter Sepulchre, and to replace the earlier

example still seen a little to the east as a small recess ornamented

with a strip of Saxon carving. Low down in the corners of the east wall

are two hollows known as aumbries which were probably used to contain

relics. In the south wall near the altar is the piscina once used for

washing the chalice and paten after Communion Services: two strips of

Saxon carving ornament the top. The blocked opening in the south wall is

thought to have connected with the lower level of the south transept.

Behind the altar the elaborately carved reredos of soft limestone is

considered to be a good example of Victorian craftsmanship, as are the

stained-glass windows.

The

South Transept

This was built by the Knights Templar in about AD 1180 as a private chapel

for themselves. Lower in the level, square and solid as a Crusaders'

castle, perhaps built by men who had fought hand to hand with the Saracens

in the Holy Land, it has its own miniature chancel and sacristy, and forms

a complete church within a church. High on the west wall is the arch of an

original Norman window discovered in 1969, and on the east wall near the

pulpit is a Norman stone carving of an Abbot. Over the south doorway the

great height of the arch is thought to have been designed to admit templar

banners. The Norman font of Sussex marble now stands on a modern pillar in

the small chancel, out of which a doorway leads to the sacristy built

between the chancels as a strong-room to contain valuables. The Templars

were exempt from all taxes, and with branches in every country in the

known world, the order became extremely wealthy and was able to organize

an international banking system. The English headquarters in the Temple

Church in London contains an underground chapel in which even the crown

jewels were on occasion deposited as security for loans. When it became

clear that the Crusades were to all practical purposes ended, governments

throughout Europe looked critically at the wealth of the Templars and

began to make political attacks. Although individual Templars owned no

personal property, many were martyred, and in England soon after AD 1308

the Order had almost disappeared.

In AD 1324 a statute of Edward II accepted the international ruling of the Pope who had formally dissolved the order that all Templar property must be assigned to another Order of Crusaders, the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, often known as the Knights of St. John or the Hospitallers, who were held in high esteem. The new owners opened the Templar Chapels to the local people and built themselves a new chapel north of the tower.

At the time of the Reformation the Order of St. John was dissolved by Act of Parliament under Henry VIII in 1540 and the new chapel later fell into picturesque ruin. Some of the stones were re-used when a south porch was added during the late Tudor period.

The Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem was re-founded in England in 1831 as a charitable and benevolent organization, and received a Royal Charter from Queen Victoria in 1888. It is probably best known today for the valuable work of its Ambulance Brigade. In 1963, the Order was re-instated as Patron of the Church at Sompting.

Sources

William Addison (1982) Local Styles of the English Parish Church

Mervyn Blatch (1974) Parish Churches of England

Russell Chamberlin (1993) The English Parish Church

A.W. Clapham (1969) Romanesque Architecture: Before the Conquest

G.H. Cook (1961) The English Medieval Parish Church

J. Cox (1944) The Parish Churches of England

P.H. Ditchfield (1975) The Village Church

G.M. Durant (1965) Landscape with Churches

Stanley P. Excell (1979) Sompting Parish Church: A Brief Guide

Eric Fernie (1983) The Architecture of the Anglo-Saxons

Richard Foster (1981) Discovering English Churches

G.N. Garmonsway (1990) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

F.E. Howard 1936) The Medieval Styles of the English Parish Church: A

Survey of their Development, Design and Features

Leonora Ison & Walter Ison (1972) English Church Architecture

Through the Ages

Nigel Kerr & Mary Kerr (1982) A Guide to Anglo-Saxon Sites

H.M. Taylor & Joan Taylor (1965) Anglo-Saxon Architecture, Vol. 1

H.M. Taylor (1978) Anglo-Saxon Architecture, Vol. 3

David M. Wilson (1986) Anglo-Saxon Art: From the Seventh Century to

the Norman Conquest

Article by Stephanie James

Part

1: History of the Church

Part 3: The Rhenish Helm