EBK Home

Kingdoms

Royalty

Saints

Pedigrees

Archaeology

King Arthur

Adversaries

For Kids

Mail David

Roman Times

The

City of York began life in the time of the Romans. The Vale of York had

been inhabited quite intensively since prehistoric times, but it took the

Romans, with their unerring eye for a good site to see the advantages of

York's position - the tidal nature of the River Ouse, which enabled ships

to reach it by sailing in through the Humber estuary, York's natural

placing as the hub of routes crossing from all points of the compass and

its elevation above the surrounding plain, which meant that it was dry,

despite its proximity to the river, and easily defensible. They called

their new settlement Eboracum, a latinized form of an old Celtic

word probably meaning "Place of the Yew Trees".

The

City of York began life in the time of the Romans. The Vale of York had

been inhabited quite intensively since prehistoric times, but it took the

Romans, with their unerring eye for a good site to see the advantages of

York's position - the tidal nature of the River Ouse, which enabled ships

to reach it by sailing in through the Humber estuary, York's natural

placing as the hub of routes crossing from all points of the compass and

its elevation above the surrounding plain, which meant that it was dry,

despite its proximity to the river, and easily defensible. They called

their new settlement Eboracum, a latinized form of an old Celtic

word probably meaning "Place of the Yew Trees".

In AD 70, nearly thirty years after the Romans' initial invasion of Britain, a strategic alliance with a federation of Northern Celtic tribes, known as the Brigantes, began to break down. The Roman governor, Petillius Cerialis, was ordered to march north from Lincoln with the Ninth Legion Hispana and crush these potential enemies. The Brigantes were to fight hard, but futilely to expel the Roman intruders, who constructed their first fortress at Eboracum in AD 71, even before they had totally subjugated Yorkshire. This rectangular 'playing-card' construction consisted of a V-shaped ditch and earthen ramparts with a timber palisade, interval towers and four gateways. It covered about 50 acres of a grid-plan of streets between timber barrack blocks, storehouses and workshops. More important buildings included the huge Headquarters Building or Principia (whose remains are on view in the Minster Foundations), the Commandant's House, a hospital and baths. The fort was designed to house the entire legion - up to 6,000 men - and remained a military headquarters almost to the end of Roman rule in Britain.

The fortifications at York were strengthened around AD 80 by a caretaker garrison while the Ninth Legion campaigned with the governor, Julius Agricola, in Wales and Scotland. The original fort was replaced, in AD 108, by a massive stone structure with walls that survived the centuries to be used as part of the defences of Viking and Medieval York. The Roman fortress even influenced the layout of York's streets in later centuries, an influence that survives to this day. In AD 118, there were further military clashes with the Northern Celtic tribes, though the Ninth Legion's exact involvement is unknown. Four years later, they were withdrawn from the province when the Emperor Hadrian toured Britain and almost certainly visited York to personally oversee the installation of the Sixth Legion Victrix in the citadel. They later helped build the great wall named after their patron, from the Salway to the Tyne.

Further tribal unrest at the end of the 2nd and beginning of the 3rd century led to the rebuilding and strengthening of many military installations in Northern Britain. This was particularly necessary at York which appears to have been overrun in AD 197. The stone walls there had such poor foundations that in some areas they had partially collapsed. Celtic resistance north of Hadrian's Wall continued and, eventually, the Emperor Septimus Severus decided it was time to punish the natives once and for all. In AD 208, he and his son, Caracalla, set up the Imperial Court it York and from here, Severus ruled the entire Roman Empire for three whole years while campaigning in what later became Scotland. Worn out by his efforts, the Emperor actually died in the city in February AD 211, traditionally somewhere in the area of Goodramgate. He was cremated in York, but his ashes were sent back to Rome. Caracalla subsequently forced the Caledonian tribes into advantageous peace-treaties.

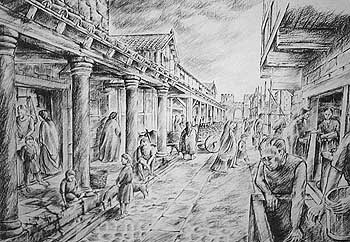

Roman York, however, was not just a garrison settlement. Across the Ouse, to the south-west, lay a major Roman town, with typically Roman accoutrements - public baths, public buildings, temples to a variety of Roman gods, shops, a water supply, drainage, sewers and houses, some luxurious with underground heating, mosaic floors and marble panelling. It had quickly become a thriving port, handling olive oil, wine, red Samian ware from Gaul, fine tableware from Germany and supplies of grain, pottery and horses for the army. Roman tombstones show the cosmopolitan nature of the city with merchants from Gaul, Sardinia and elsewhere. Around AD 200, it had been made the capital of Britannia Inferior (Upper Britain) - and therefore seat of the governor or praeses - when Britain had been divided into two provinces; and it was probably during Severus' time in the city that York was given the status of a Colonia (though it may have already been a self-governing Municipium). This was an honourary title which had, by this time, lost its original military veteran connertations and instead indicated that York was the amongst the most important towns of the Empire.

A century later, during the usurpation of the British Emperor Allectus, Diocletian further divided Britain into four small provinces during his search for improved administrative effectiveness. Though the administration was not established until the Western deputy Emperor, Constantius, had re-established Roman Imperial power in AD 296. By this time, Pictish warriors appear to have raided as far south as York and Chester and Constantius probably visited the city before campaigning north of Hadrian's Wall. York remained a provincial capital, this time of Britannia Secunda (Secondary Britain) and the commander of the Sixth Legion was made governor. The name of only one governor is known - Aurelius Arpagius. The office held by this man was therefore in charge of both civil and military matters in the province. However, around AD 300, possibly as a result of Constantius' campaigns, the governor's military powers were given away to the Dux Britanniuarum, a new position created to command the Roman frontier along Hadrian's Wall and throughout Northern Britain. His headquarters was at York and the fortress defences and much of the city appears to have been rebuilt in a much grander scale for his benefit.

Constantius certainly returned to Britain and his Caledonian conquests in AD 306, for he died in York on 25th June that year. His son, Constantine, who was campaigning with his father, was immediately heralded in the city as the new Emperor by his troops; and after defeating rivals on the Continent, he became one of the Empire's greatest rulers. His statue can be seen near the Minster's south transept. It was Constantine the Great who became the first Christian Emperor and in AD 312 declared religious toleration throughout the Empire. Only two years later, three British Bishops attended the Council of Arles. One, Ebraucus, came from York, showing the speed at which the new religion had spread. The site of this man's cathedral has not yet been discovered.

At the time of Constantine's push for the Imperial Crown, one of his greatest supporters in York was one "Crocus, King of the Alemanni," almost certainly the leader of the Germanic foederati settled in the Vale of York and Wolds of East Yorkshire. These continental warlords were given areas of farmland in return for military service from at least the early 4th century. In AD 367, during "Great Barbarian Conspiracy," Pictish and Scottish warriors poured into the province over Hadrian's Wall, helped by rebellious Germanic mercenaries in the Roman army. At this time, even the Dux Britanniarum was of Gothic extraction, a man with the Latinized Germanic name of Fullofaudes. He was almost certainly a Rhinelander or Romano-Vandal recruited as a commander in the Roman army as part of the normal Imperial policy. He was ambushed and captured by his countrymen. An interesting situation which was planting the seeds of events to come in York.

The Roman General Theodosius was sent to crush the Anglo-Pictish onslaught and this he did to great effect. It is not known whether York was attacked at this period, but the general, no doubt, patched up the city's defences as he consolidated fortifications throughout the north. This may have included the erection of the so-called 'Anglian Tower' in the city. However, despite this return of calm, civil wars amongst rival Emperors on the Continent began to weaken the Imperial hold on Britain. The British claimants Magnus Maximus and Constantine III withdrew the last remaining troops from Britain in AD 383 and 407 respectively. The Sixth Legion left York for the Continent and by AD 410, the Emperor Honourius had instructed Britain to look to its own defences.

Article by Brenda Ralph Lewis & David Nash Ford

Next: Dark Age Times